State Approaches for Promoting Family-Centered Care for Pregnant and Postpartum Women with Substance Use Disorders

October 02, 2019

The use of opioids and other substances during pregnancy has increased significantly in the past decade, and so too have complications from their use. According to CDC, national opioid use disorder rates for hospital deliveries more than quadrupled between 1999 and 2014, corresponding with increases in nationwide rates of neonatal abstinence syndrome. Opioid and substance use disorders (SUD) continue to affect families beyond pregnancy; in 2017, about one in eight (8.7 million) U.S. children lived in a household where at least one parent had a SUD in the prior year.

Given addiction’s far-reaching impacts on families, a 2019 report from HHS’ Assistant Secretary for Planning and Evaluation (ASPE) recommends a family-centered approach that supports pregnant and parenting women living with SUD—many of whom also are their family’s primary caregivers—along with children and other family members who may be exposed to the effects of addiction. This brief highlights state approaches for promoting family-centered treatment to meet the complex needs of pregnant and postpartum women living with SUD and their families.

What Is Family-Centered Treatment?

What Is Family-Centered Treatment?

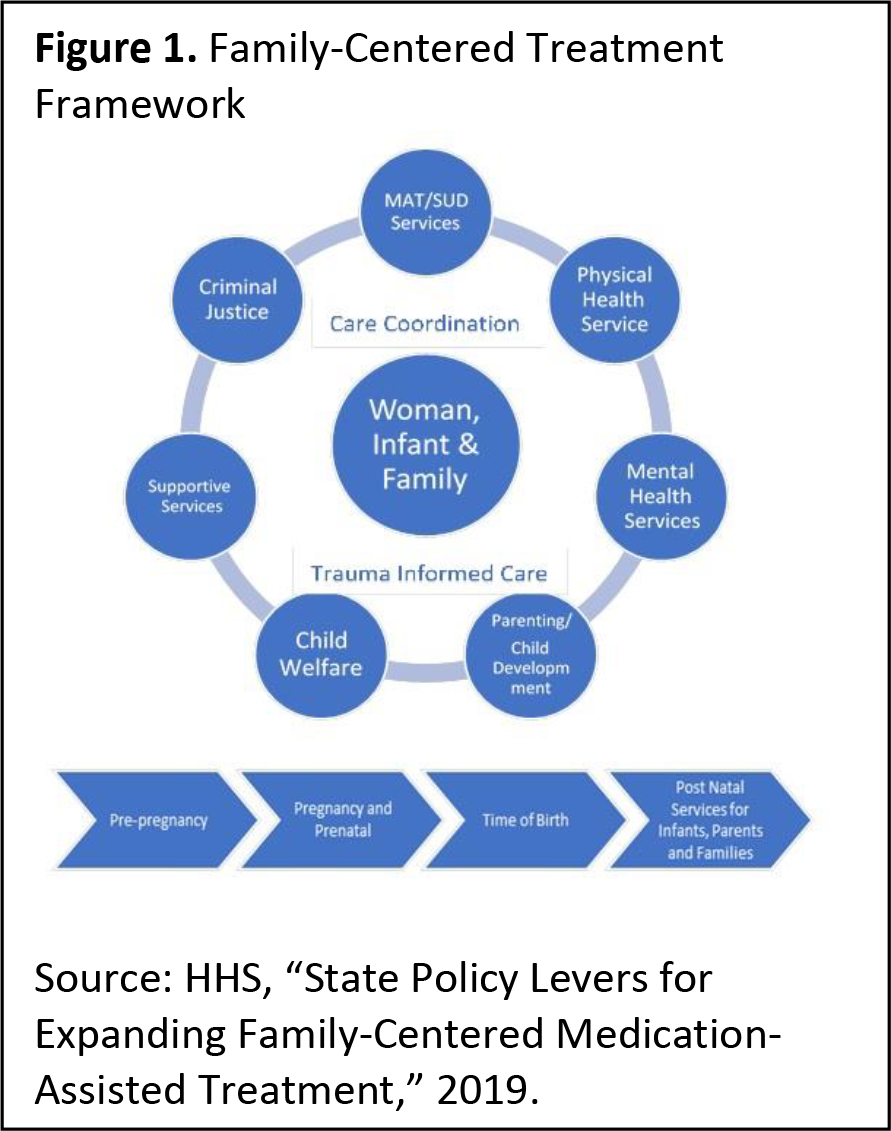

Family-centered treatment assures that pregnant women, moms, infants, and families receive an array of coordinated services to support them during a mother’s recovery. A family-centered framework involves children, partners, and other family members in the treatment process and assures that family members receive the health care and community-based supports that can help them thrive. For example, a family-centered approach may integrate Screening, Brief Intervention, Referral and Treatment (SBIRT) in maternity care clinics, coupled with long- term follow-up and home visits to assure that mom and baby receive necessary resources. At the time of birth, a family-centered inpatient approach co-locates mothers and infants after delivery, a best practice known to improve maternal and infant outcomes.

Unlike traditionally fragmented systems of care— under which many women too often fail to receive needed services and follow-up care—family-centered treatment relies on care teams or managers to coordinate care and transitions across clinical and non-clinical services that may be needed during pregnancy and beyond. As shown in Figure 1, this may include medication-assisted treatment (MAT) and SUD services, physical and mental health services, parenting and child development services, and linkages to other supports, such as child care, transportation, housing, employment training, and parental education.

State Approaches for Promoting Family-Centered Treatment

States develop and implement family-centered treatment through a variety of means, including state amendments, Section 1115 waivers, laws and policy measures, and state funding for family-centered programs. A couple successful examples of these initiatives include:

- Launched in 2017 to address what health secretary Rachel Levine called “the biggest public health crisis we face here in Pennsylvania—and in the nation,” Pennsylvania’s Centers of Excellence (COEs) program coordinates “whole-person” care for individuals with SUD and their families with the goal of integrating behavioral health and primary care. Seven of the state’s 45 COEs meet the unique needs of pregnant and postpartum women. Preliminary data suggest that COEs are expanding access to treatment options and keeping clients engaged in their treatment.

- West Virginia’s Drug Free Mom and Babies program is a comprehensive medical and behavioral health program for pregnant and postpartum women. Funded by a private foundation and state agencies in 2012, including the West Virginia Department of Health and Human Resources, the program utilizes recovery coaches to coordinate medical, behavioral, and social services and assure follow-up for two years after the birth of the baby. Home visits and other services are provided to help connect women to needed resources. A 2019 evaluation found that the program was associated with reducing drug use among program completers.

Looking Ahead: Opportunities To Engage Families in SUD Treatment

States are investing federal, state, and foundation resources and using other policy tools to scale and replicate health home models in new locations across the state or statewide. For example, positive outcomes from West Virginia’s pilot project prompted state leaders to expand beyond the initial four pilot locations to 11 sites across the state in 2018. States like Pennsylvania are developing evidence- based approaches for expanding access to treatment, including MAT, and building provider capacity to deliver and coordinate care. The family-centered treatment programs in the above states emphasize the importance of transitioning women and families to essential services beyond delivery and throughout the recovery process.

Beginning in 2020, up to a dozen states will receive new federal funding to support family-centered approaches. CMS’ Maternal Opioid Misuse (MOM) Model, announced in February 2019, will support the delivery of coordinated physical health care, behavioral health care, and wrap-around services. The initiative will help state Medicaid agencies, providers, and healthcare systems transform their delivery systems for pregnant and postpartum women with SUD and reduce fragmentation in care delivery.

This publication was supported by the grant number, 6NU38OT000290-01-02, funded by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Its contents are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official views of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.